Through learning guitar chords theory, you will be able to understand how chords on the guitar are constructed, and thus have a better understanding of guitar theory in general.

As a beginner guitarist, this is not that relevant, but as you advance in your guitar studies, you will want to do more than just play chords, you’ll want to understand why your favorite songs sound the way they do, experiment with new chords, and with time, write you own songs.

To be able to understand how guitar chords are constructed, you’ll have to first be familiar with the major scale and its intervals. If you don’t know the major scale on the guitar yet, I suggest you read about it, otherwise, chord theory will not be understandable.

Major Chords (Major Triads)

Every guitar chord contains at least 3 notes. Chords that have 3 notes in them are called triads (triad means "group of three").

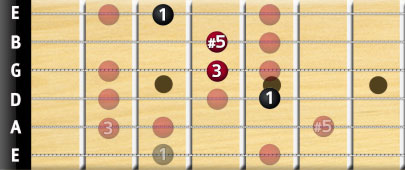

A major triad (major chord) uses 3 notes from the major scale, the Root (1), the 3rd-degree note (3), and the 5th-degree note (5). These notes will make up all major chords on the major scale, with the root note defining the label of the chord (ie. what it's called, for example, C major, G major, etc.).

Major Chord = I-III-V degree notes of the major scale

Now, if you look on the "boxed" E string major scale, the first occurrence of the 3rd and 5th lie on the same string, so to create a chord where all 3 notes can ring out, we need to use the higher 3rd on the G string.

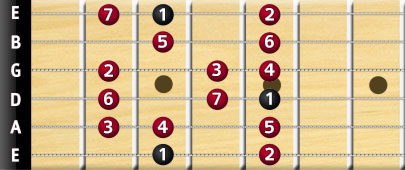

To understand this, let's have a look at the most well-known major scale shape, rooting on a G note on the low E string.

Remember the G major fingering?

As we just learned, the 1st, 3rd, and 5th-degree notes make up a major chord. Since our root note is the G, its 3rd degree will be a B, and its 5th degree will be a D.

1 W 2 W 3 H 4 W 5 W 6 W 7 H 8(1)

=

G W A W B H C W D W E W F# H G

Now have a look at the scale shape again, notice the fingering, and that even the open D and G strings are in the triad, since the 1st and 5th-degree notes at fret 5 of strings A and D are the same as their neighboring open strings.

If you were to use this same scale shape and play the G major chord as a bar chord, you would be using these notes from the major scale, resulting in a higher voicing of the G major chord:

This triad is of course applicable on all major scale shapes, so if you were to use a shape that roots on the A string, you would apply the 1st, 3rd, and 5th degree notes and get the major chord, as with this C chord:

Again, remember the C major fingering, and recognize that’s it is the triad pattern in the major scale. The open strings are triad notes as well. If you take the same scale to a higher voicing, you will arrive at the C major bar chord.

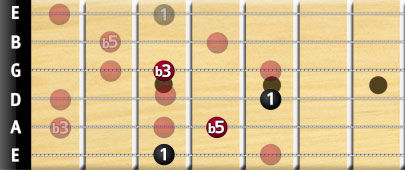

Minor Chords

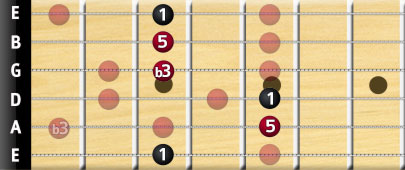

Minor chords on the guitar, also called minor triads, are constructed the same way, the difference is the minor sound, which is always a flat third-degree note in minor triads:

Minor Chord = I – b III - V degree notes

So minor chords are the root note, a flattened third note (1 semitone below the regular 3rd degree), and the fifth note of the major scale.

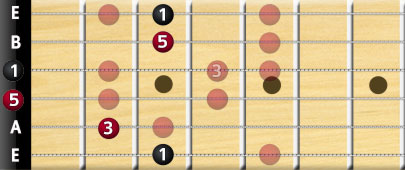

As such, let's return to our original G major chord example, and transform it into a G minor chord.

We have to flatten the 3rd-degree note, which brings us to a small limitation of the G minor chord, since the open string chord fingering is hard to produce. Because of this, we mostly use the minor bar chord fingering:

The same applies to the C. We simply use a flattened third to sound a minor C chord, here it is as a barre chord:

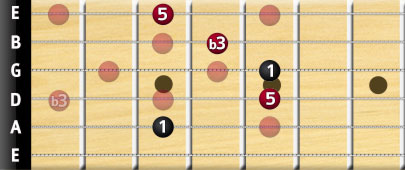

Suspended (Sus) Chords

You have probably played suspended chords already, now it's time to find out how they are built.

With suspended, the 3rd-degree note is left out of the triad, and is replaced by the note specified by the chord, which will be either a 2nd or 4th-degree note on the major scale:

Sus4 Chord = I – IV - V degree notes

Sus2 Chord = I – II - V degree notes

Let's return to the G bar chord example again, and transform the G major bar chord into a Sus4 chord. We know that the interval on the major scale between the 3rd and 4th-degree notes is 1 semitone (half-note), so if we would be transforming a major chord that uses third degree notes, we would have to simply move up from the 3rd degree note one semitone to the 4th degree note to construct a Sus4 chord.

So to put it simply, we replaced the 3rd by the 4th note in the major scale.

Try arpeggiating it, then play the major chord. You’ll see that the sus4 chord will sound unfinished by itself, but if you resolve to the major, it’ll be just right.

Try this with other chords as well, for example, the D major and the Dsus4. Try hammering onto the 4th degree and pulling back onto the major triad 3rd degree.

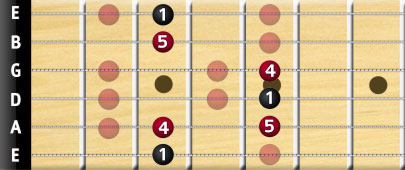

Augmented Chords

Augmented guitar chords are triads as well, which means that they will contain 3 notes from the major scale. Augmented chords are used in jazz and blues very often, so if this is your musical style, you’ll love these chords.

Augmented chords are similar to major chords, with the exception that the 5th degree is raised 1 semitone (half-note), so it’s a sharp 5th note on the major scale.

Augmented Chord = I – III - #V degree notes

Looking at the G chord again, the augmented chord shape will look like this:

Notice that we leave the B and E strings out of this chord shape. This is because it would be too hard to finger, but since these notes are already played in this voicing, there is no problem if we omit them. If you wanted to arpeggiate this chord, you could use the omitted notes, since you won’t have to hold down every string during an arpeggio. Try it out!

Alternatively, if we wanted a higher voicing of the G augmented chord, we could play these notes instead:

So all you’ll need to remember, is that augmented chords have a sharpened 5th degree note, as compared to major chords. And as always, you can use this anywhere on the fretboard, as long as you stick to the predefined intervals.

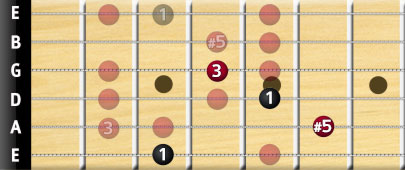

Diminished Chords

Diminished chords are made up of 3 notes as well, so they are triads. They resemble minor chords, in that they have a flattened 3rd degree, the difference is that their 5th-degree note is flat as well.

Diminished Chord = I – bIII - bV degree notes

Let's look at a diminished chord built around the E-shape (E string root note)

Again, notice how we omit the notes on the 2 highest strings, simply because it would be impossible to finger as a chord. But again, as with the augmented chord, if you wanted to play an arpeggio over this chord, you could use the notes on the strings you would otherwise omit from the chord fingering.

So all-in-all, a diminished chord is just a minor chord with a flat 5th degree. This is the easiest way to remember it, just like with the augmented chord, which is a major chord with a sharp 5th degree.

7th Chords on the Guitar

We’ve been covering triads until now, but of course, there are guitar chords that have more than 3 notes.

The first set of chords with 3+ notes we’ll look at are 7th chords.

Why are they called 7th? Because the fourth added note will be the 7th-degree note on the major scale. Pretty simple!

7th chords have several variations, as did the triads, lets have a look one-by-one.

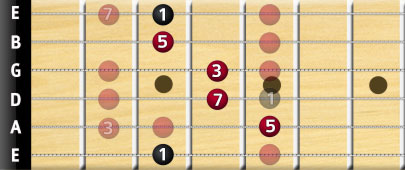

Major 7 chords

Major 7 chords are pretty straightforward, they are merely major chords with an added 7th note. These chords are used in jazz very often.

Major 7 Chord = I – III – V – VII degree notes

So if you know the major scale (and you should already), constructing 7th chords is simple. Let's look at the G example again:

So this is a G Major 7 or Gmaj7. Notice that to add the 7th-degree note to the otherwise major chord shape, we moved 1 semitone lower from fret 5 string D, which was a G note. Of course, this is not a problem, since it was a second root and there are still 2 other instances of the G note in the shape.

This is another aspect of building chords that you’ll instinctively get familiar with, once you know the major scale and the chord “equations”. You’ll have to sacrifice notes that would otherwise still be in the chord, because you need to replace them to make room for notes you could otherwise not add.

You could get many-many voicings of the same chord, just from playing around with this.

Dominant 7 Chords

We’ll look at the dominant 7 chords next, which are widely used in blues music. The only difference from the major 7 chord is that the dominant 7 uses a flat 7th-degree note. You’ll come across dominant chords often, so just remember that whenever a chord is dominant, it will have a flat 7th-degree note.

Dominant 7 Chord = I – III – V – bVII degree notes

Another important thing about dominant chords is their notation. When you see G7 for example, it means G dominant 7. There is no added notation between the letter and the number. So unless otherwise noted with a “maj” prefix, if you just see 7 beside a root note, it will mean a flattened 7th note.

Let’s look at our classic G chord example. But no… we can’t, the fingering wouldn’t work. Instead, we’ll revert to the open string G chord, and turn it into a G7 by adding the flattened seventh note from the major scale:

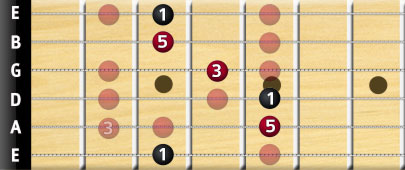

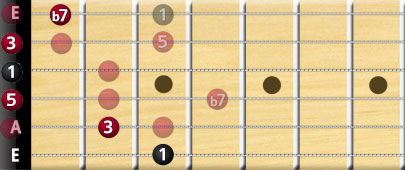

Minor 7 Chords

Minor 7 chords are similar to the dominant 7 chords above, the only difference is the flattened 3rd-degree note, transforming the chord into a minor chord. As you'll recall, if a chord has a flat 3rd degree, it will be a minor chord.

Minor 7 Chord = I – bIII – V – bVII degree notes

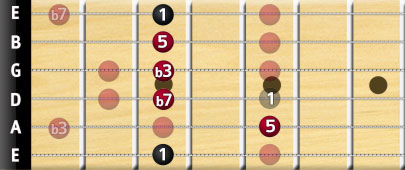

We can return to the G bar chord again, it would look like this:

The notation for minor 7th chords, with the G as our example, will be G minor 7 or Gm7.

Again, if you would want to play an arpeggio based on the notes of this chord, you could use every note the chord uses, so the 1st, flat 3rd, 5th and flat 7th notes along the shape. Remember, as long as you stick to the intervals as specified, you will play the correct note.

Augmented 7 chords

Augmented 7th chords are similar to the augmented triads we learned about earlier, the only difference is that we’ll be adding a fourth note, as with all 7th chords. Now if you’ll remember, the augmented triad was the 1st, 3rd, and sharp 5th-degree notes. To turn this into an augmented 7 chord, we’ll have to add a flat 7th-degree note.

Augmented 7 Chord = I – III – #V – bVII degree notes

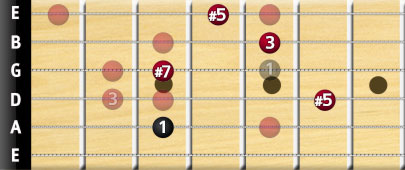

We can’t demonstrate using the good old G, so we’ll use string A fret 3, a C note as our root, and build the chord from there.

Remember that it's all about intervals. If you have your root, just count the intervals along the strings diatonically, and you’ll have the chord.

The above diagram is thus a C Augmented 7 (also written Caug7). It’s a bit tricky to finger, since you have to hold a bar across the third fret, try it out. Alternatively, as with all our chords, you could arpeggiate the notes of the chord.

So just remember, “augmented” refers to the augmented triad, and the "7" refers to the flat 7th note added to the triad.

Half Diminished Chords

Half diminished chords are 7th-degree chords, and include the root, flat 3rd, and flat 5th just like a regular diminished triad, but also adding a flat 7th note.

Half Diminished Chord = I – bIII – bV – bVII degree notes

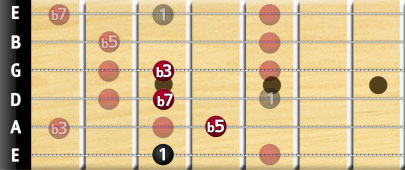

Sticking with the G, it would look like this:

The above is written as Gm7b5. Just remember the denotation, it's actually easier to see what’s going on with this chord from the written notation. The “m” is short for minor, meaning a flat 3rd, the “7” means a flat 7th, and the “b5” means flat 5th.

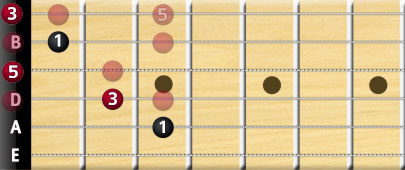

Diminished 7 chords

Diminished 7th chords are based on the diminished triad, as the first 3 notes are I, bIII, bV, but you’ll also be adding a double flat 7th note.

Diminished 7 Chord = I – bIII – bV – bbVII degree notes

Yes, double flat! You flatten the 7th-degree note twice, so it would actually be a 6th-degree note, but most musicians use the double flat notation since it’s a 7th chord and is easier to remember this way.

You may be thinking "well, that double flatted 7th is now in the position of the 6th note in the major scale" - well you're absolutely right, but in this context with the 5th being flattened into a diminished position, the rules of music take over to highlight the context, a double-flatted 7th note, a diminished 7th in relation to the natural dominant 7th position (which was a flat 7th, to begin with!)

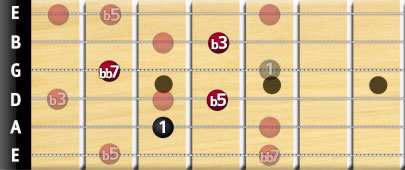

Let's look at an example, we’ll use the C root, so this will be a C diminished 7 (Cdim7):

As you can see, neither of the E strings are used in this fingering. If you were to play an arpeggio over the notes of this chord, you could use the relevant notes on the E strings without a problem.

Extended Chords

Now that we’ve looked over triads, which have 3 notes, and 7th chords, which have 4 notes, we will touch on chords that use even more notes. These are called extended notes. Extended chords are used to create fuller sounding chords.

First of all, you’ll need to know the order of chord tones. As you know, the musical alphabet starts over 1 octave above the root, so when we reach the 8th degree on the major scale, we start the numbering over, since the 8th degree will be the original root note 1 octave higher, the 9th degree would be the 2nd note, the 10th degree would be the 3rd note, the 11th degree the 4th note, the 12th degree the 5th note, the 13th degree the 6th note…

So to make it short, the cycle looks like this:

| 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 13 |

| Root | 3rd | 5th | 7th | 9th | 11th | 13th |

| (4th) | (6th) |

When you construct extended chords, you can use the 9th, 11th (4th), and 13th (6th) degree notes as well.

You’ll need to remember, that when you see a notation for a chord, only the highest degree is noted. So if you had to build a G9 chord, you would know that it contains every degree up till the 9th note on the major scale note, like this:

| 1 | 3 | 5 | b7 | 9 |

| Root | 3rd | 5th | flat 7th | 9th |

ADD chords

Contrary to the above, if we cannot add all of the notes to a chord and have to leave one out of the natural progression as per the major scale, we call these chords add chords.

For example, an add9 chord will have the following interval pattern:

Add9 Chord = I – III – V – IX degree notes

11th and 13th chords

Once we start pumping in more and more notes, we will inevitably run into more and more tones that we just cannot have in the chord, if we want to play the higher degree notes as well. What to do?

- As a rule of thumb, you’ll usually want to leave out the 5th degree note when this happens.

- The more notes you add, the more likely that one of the notes will unharmonious with the rest of the chord. Just leave that note out. Remember, that if it sounds good, it is good!

- With 13th chords, we usually leave the 11th degree note out.

Amazing, very clear and useful. Added to bookmarks. Thanks a lot!

Hi Bruno,

To understand chord construction, you first need to be familiar with:

– the musical alphabet (https://www.theguitarlesson.com/guitar-theory/guitar-notes/)

– the major scale (https://www.theguitarlesson.com/guitar-theory/guitar-scales/major-scale/)

Please read those articles, understand them, and revisit this page. It will make sense after.

Tom

Lost my first attempt at articulating my problem. In a nutshell, after you determine the root, how does the sequence of other numbered notes work to create the triad. I don’t understand how to use all the other notes in that diagram? How do I proceed to create the chords out of the other numbered notes in the diagram?

What do the ‘W” and ” H” mean?

Read Tom’s links above

w=whole step or tone

h=half step or semi-tone

Startng on the E string, 1st fret is a half step F, Open E to 2nd fret is a whole step F#, Open E to 3rd fret is whole and a half step, and so on. So in a major scale w-w-h-w-w-w-h So the E major scale is

E-F#-G#-A-B-C#-D#-E. Remember there is no such thing as E# and no B#.

E is I, F# is II, G# is III, A is IV, B is V, C# is VI, D# is VII. So an E major chord is E-G#-B